Ruth Ann Miller Memorial, Tamarack Mine Shaft #4

Today, Tamarack Mine Shaft #4 is a memorial to Ruth Ann Miller, a 7-year-old girl who fell to her death in the mine in 1966. Before diving into her story, we must go back nearly a century.

This isn’t a happy story. The paragraphs below describe the harsh realities of working in a copper mine at the turn of the century and reference numerous deaths, so scroll cautiously.

Or, jump to the story of Ruth Ann Miller.

The History of the Tamarack Mining Company

The Tamarack Mining Company was fully operational by 1885, having started in 1882 with the idea to dig extraordinarily deep mine shafts to tap the Calumet and Hecla Conglomerate Lode on the outskirts of Calumet and Hecla Mining Company property. According to an August 1885 piece in the Detroit Free Press, tapping the lode “has cost about $192,000, or within the estimate of $200,000, and that the work had been accomplished within the estimated time.”

The mine would have some of the deepest shafts in Copper County and be one of the most profitable for a time.

Though Ruth Ann Miller is the most known fatality that the mine produced, she was far from the only person claimed by the Tamarack Mine. The following isn’t meant to diminish her story but is presented as a reminder that wealthy men who never lived in the Upper Peninsula made astronomical profits off its mines and lumber without proper safety measures in place, even decades after the mines closed. The following information isn’t a complete history or death record of the Tamarack Mine, but is what I could find in newspaper archives.

John Ribandi was killed while working in the mine on June 29, 1886, by a falling rock. Valentine Donsuch fell 2,000 feet into the mine on November 25 and was crushed.

Leonard Johnson died on May 5, 1887, inside the mine. On Monday, September 19, four miners were severely injured inside the mine “by the fall of a staging,” according to the Lansing State Journal. On October 15, Richard Resentally fell 200 feet into the mine and died.

On May 10, 1888, James Shea was killed after falling under a locomotive as it backed up towards the Tamarack Mine. On August 25, Joseph Simmons fell 25 feet in the mine onto his skull, dying.

On November 25, 1889, Thomas Moore fell while riding the bucked to the bottom of Shaft No. 3, dying instantly.

Samuel Hocking and Fred Lawrence were killed on April 22, 1890, after an explosion went off prematurely in Shaft No. 1.

On April 27, 1890, there was a fire at Shaft No. 3 at three o’clock in the morning. At the time of the fire, John Williams, a pump man, was at the bottom of the shaft. Captain Joseph Herbert, John Thomas, John Rowe, and Thomas Bell went in looking for Williams. Belle ascended after the smell of gas became too powerful. Two of the miners suffocated, and John Pentecost arrived on the scene, going into the mine alone and hoisting Rowe and Herbert to the surface of the mine. Rowe died, Herbert recovered, Thomas’ recovery was doubtful, and Williams’ body was found the next day. According to the Detroit Free Press, “The widows are crazed with grief. Hundreds visited the scene of the disaster to-day.”

In June 1890, nearly 1,000 miners went on strike at the Tamarack Mine, demanding a ten percent raise and an eight-hour workday. The strikers marched onto company property and ensured that the scabs who had taken their place could not do any work. It’s unclear if the workers got what they were asking for.

On December 17, 1890, Captain Roberts was killed in the Tamarack Mine after his head was crushed by machinery. He left behind five children.

In February 1891, Peter Miker ‘walked into a shaft at the Tamarack Mine,’ according to the Niles Daily Star, dying and breaking every bone in his body in the process. On February 28, Carel Navarain, an Austrian miner, was killed in Tamarack Shaft No. 1 by falling trap rock. On March 24, an unexpected explosion took the lives of Samuel Hocking and Fred Lawrence. On October 28, Thomas J. Waters, an Englishman, was crushed to death by falling rock. On December 9, Matt Flink and Olaf Ericson were killed by an unexpected explosion at the Tamarack Mine.

In March 1892, an unnamed Austrian miner was killed by falling timber at the foot of one of the Tamarack shafts. Erick Saariniemi, a trainman, was killed in the mine on July 1 after rock fell onto him. On July 25, Richard Thomas was killed on the 14th level of the mine. On September 29, a large rock fell and killed Sylvester Ambrosich, an Austrian.

On April 12, 1893, Peter Larauner had his arm ripped off while oiling an engine. On May 15, John Bankstrom, a timberman, was killed in the mine. On May 19, an unidentified Polish man was killed by a falling timber at the Tamarack Mine. In early July, Charles Maguine, an Italian, was killed by falling rock. On August 10, a Cornish man named Alfred Tucker, who had only been in the United States for a few months, was killed by falling rock in the mine. On August 12, Michael Shuick fell 400 feet into the shaft and died. At Shaft No. 2, John Hosking was killed on September 4, having his head blown completely off by flying rock from an explosion. In November, Nicholas J. Andrews and Henry Trevernow were killed by falling rock.

In January 1895, Jacob Hedela, a Finn, was struck by a large piece of falling rock and died. In February, the dry house at the North Tamarack Mine burned, netting the company a $4,000 loss. In March, Jacob Brula, an Austrian, died after being struck by falling rock. In April, Peter Garyntyztis, a Pole, was killed after falling rock hit his head. He had six children. The next day, John H. Heikka, 29, was killed in Shaft No. 2 after an accidental fall. That same month, Joseph Sleman was overcome by smoke and died from inhalation. In early June, William Holmes fell 800 feet to his death in the Tamarack Junior Mine. In September, John Torlina and John Benchichki were crushed by a collapse, and Michael Michelchick broke his leg. That same month, Michael Beuttch and John Vogina died on the 20th level of the mine. On November 7, Samuel Kent and John Polkhinghorne were “blown into mincemeat” at the Tamarack Junior Mine, according to The Herald-Palladium, dying instantly.

In February 1896, Richard Little fell in the Tamarack Junior Mine and fractured his spine, dying in early March. On June 24, Henry ‘Harry’ Trevarrow died in a stope south of Staft No. 2 on the 20th level. He was hit by a falling piece of rock and died as his coworkers were assisting him. He had two children. In July, John Shutz and John Ericson were severely injured after a powder explosion. On August 7, the Shaft No. 1 Shaft House was struck by lightning, causing a minor fire. On October 29, Peter Ripa, a Finn, died at the Tamarack Junior Mine. On December 1, Mat Baghor, an Austrian timberman, was killed by falling rock at Shaft No. 2.

In February 1897, a fire at the Tamarack Mine left several men trapped inside. Those stuck were Peter Lempea, William Lempea, William Thomaszkoski, and Antoine Thomaszkoski. The Thomaszkoski’s were found dead, and the Lempi’s were saved. Peter Lempea later died from pneumonia from his time in the shaft during the fire. He had ten children, including his son, William, who was rescued with him. On April 1, Mike Witmore, an Austrian, fell some forty feet down Shaft No. 2 to his death. The same week, Michael Warner was killed by falling rock in the mine. In July, John Buschan died from injuries sustained in the mine. On July 20, Frank Benlf, an Austrian, was severely injured and would likely not recover. Frank Mozchess was also wounded but was set to recover. On September 13, Charles Jacobson was killed in the mine, and Jacob Kurnen was struck by falling rock on September 16, killing him instantly. In October, John H. Johnson was killed in the mine by falling rock. On November 8, John Doyle was killed after his head was crushed between the oil box and the ties on the tracks of a flat car.

On June 3, 1898, Frank Ronak was struck with rock from a blast in Shaft No. 2 and died. In early September, John Goldsworthy was killed by an explosion. Jacob Kraft was severely injured, too. In late September, Jerry Sullivan broke his back after being hit by falling rock. He wasn’t expected to survive. According to the L’Anse Sentinel on October 8, 1898, the Tamarack Mine was worth “$10,000,000, has paid dividends of $5,330,000, and employs 1,600 men.” Less than two weeks later, Louis Grenet was killed by falling rock. According to the Detroit Free Press, there were six similar deaths in Copper Country that week alone. A few days later, John Zolka died thanks to a premature explosion. A few days later, Louis Grenet, 19, was killed by falling rock.

In early February 1899, Edward Hawkins fell nearly 4,000 feet into the mine shaft. According to the Ironwood Times, “only fragments of his body could be found.” In October, Henry Hammerstone died after being hit with falling rock.

In the early 1900s, the Tamarack Mining Company had a baseball team, which was typical for mines of the era. They were once a member of the Copper Country League and later the Copper Country Junior League. The mining company also had a bowling league.

On January 10, 1900, Joseph Hodges, 26, was caught by a hanging rock. He was taken to the hospital, where he died. John Mulvey died on February 15 after an accidental fall. On April 12, George Kopp died in the mines, and his partner, Joe Sunich, was severely injured. That same week, John Matta and Richard Hill died after a powder explosion in the mine. According to the Detroit Free Press, there were four deaths at the Tamarack Mine that week alone. Vincent Chopp, 20, died after being pummeled with rock a few days later. On May 17, Joseph Rostich died after getting caught between the cage and timbers, falling some 120 feet. Lazerus Teto was killed by a skip in mid-September. William Lane, 42, was killed by falling rock in mid-November.

In August 1901, falling rock killed three men and injured two more in Shaft No. 2. Richard Trezona, John Simmons, and Matthew Stainhoa died, and Samuel Jacobsen and Matthew Amala were injured. A few days later, Sommut Hyvarinen died from injuries related to the accident. Matthew Amala later died, too.

In January 1902, Joseph Plese died in the mine after falling a few hundred feet. In August, John Gurich died. On September 24, Martin Verbantz fell out of a cage and descended to his death. John Varvanitze fell some 2,000 feet a few days later, dying instantly.

Paul Lackner, 30, was killed by a falling rock in May 1903 by falling rock. He had several children. Thomas Gregarovitch was torn to pieces by a blast in mid-July. On September 9, August Nikela was killed by an explosion. On October 26, Peter Varbanich was crushed by two cars in Shaft No. 5. On November 5, Mike Klobusher was killed by a pulley block that was knocked loose and fell. He had one child.

Joseph Fordon and John Schalle were killed, and two others were injured when several tons of rocks fell from above on January 21, 1904. In late February, Mike Braska, 28, was killed by falling rock in Shaft No. 3, and multiple others were injured. In late June, Joseph Mukavas, a timberman, was killed by falling rock. In early September, John Reed and Andrew Gregoryic were killed by falling rock. In October, Mike Lamither, a trammer, was killed when rocks fell on top of him.

On January 26, 1905, Henry Aho and John Reini were killed by an accidental explosion. In February, Archie Melo died from his injuries working in the mines. On March 11, William Hawkins got caught between the cage and the shaft timbers when it started moving, causing his death. On May 19, Charles Raas fell and died in the mine. In June, Frank S. Stehar, timber boss at Shaft No. 3, fell while riding down in the cage, dying instantly. In December, Laurance Brinz, 36, was killed by falling rock in Shaft No. 2.

On January 11, 1906, Michael Simonivich, Samuel Bozovich, and John Yaksa were killed in the mine during a fire. Shafts 1, 2, and 5 were sealed with wood and clay to suffocate the fire, which burned for weeks.

Three months later, considerable gas was still left inside the shaft, preventing work and deterring the rescuing of the miners’ bodies. They were found in April.

At some point in January 1906, Lawrence Brinz was struck by falling rock and died in the Tamarack Mine. In June, Sam Matson, a timberman, was killed by a blast in Shaft No. 5. In August, Jacob Holholme, a drill boy, was struck by falling rock and died.

On March 7, 1907, Mat Takenen fell 700 feet and died in the shaft. In June, Peter Corbi was struck by a piece of rock and killed in Shaft No. 2. On July 11, Henry Newman and Theodore Koski were killed by falling rock in Shaft No. 2. On August 13, John Jelinich was working in Shaft No. 3 and was killed.

In November 1907, John Chachi and Joseph Hosich were buried by falling rock in Shaft No. 5 at the Tamarack mine. Hosich died, and Chechi may have recovered. Earlier that month, Matt Dubanic fell 400 feet down the shaft and died.

By 1908, the mine was no longer profitable. Mining continued.

On May 6, 1908, an engineer mistakenly sent the cage at Shaft No. 5 crashing into the roof of the shaft house. Inside were nine drill boys. Four of the boys were crushed so severely that they died—all sustained injuries. In August, John Bols, 21, was killed by falling rock in Shaft No. 5. Blinko Kilfish, 18, fell a thousand feet in the Tamarack Mine in October. According to the Unionville Crescent, “His remains were collected in a basket.”

In March 1909, William Polkinghorne fell a mile and died at Shaft No. 5. Earlier that month, Matt Koski, 24, was struck by a “falling piece of rock smaller than a hen’s egg,” according to the Lansing State Journey, and was killed.

In early October 1909, Henry Sobey died after an accident at the mine. On October 25, Michael Merilina, 25, fell about 80 feet in Shaft No. 5 and died. That same month, James Opal, 45, fell to the bottom of Shaft No. 5, dying instantly.

In March 1910, Reino Arfman died in the North Tamarack Mine. On June 18, James Olds was killed instantly by falling rock at the Tamarack Mine. In the early morning of July 16, 1910, John Latzala was killed by a premature blast. In late July, Abram White, 54, was struck by falling rock and died in the mine. On September 12, Eline Lebortana, 28, was struck by falling rock, dying nearly instantly.

On April 29, 1911, Samuel J. Wallace died in Shaft No. 5 after he was hit by a falling rock. In May, Anton Kresins, George Malchich, and Centon Crisnic were all killed in the Tamrack Mine.

The Tamarack Mine closed in 1913 due to the Copper Country Strike and reopened in May 1914. Employee conditions and pay didn’t improve much, though the eight-hour workday was eventually implemented. Still unprofitable, the Tamarack Mining Company sold its property to the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company in 1917, and the company folded. The Calumet and Hecla Company used the mine for a few more years.

The Tamarack Mine’s five shafts were capped and abandoned and, over the years, somewhat forgotten as the shaft houses were demolished.

The Story of Ruth Ann Miller

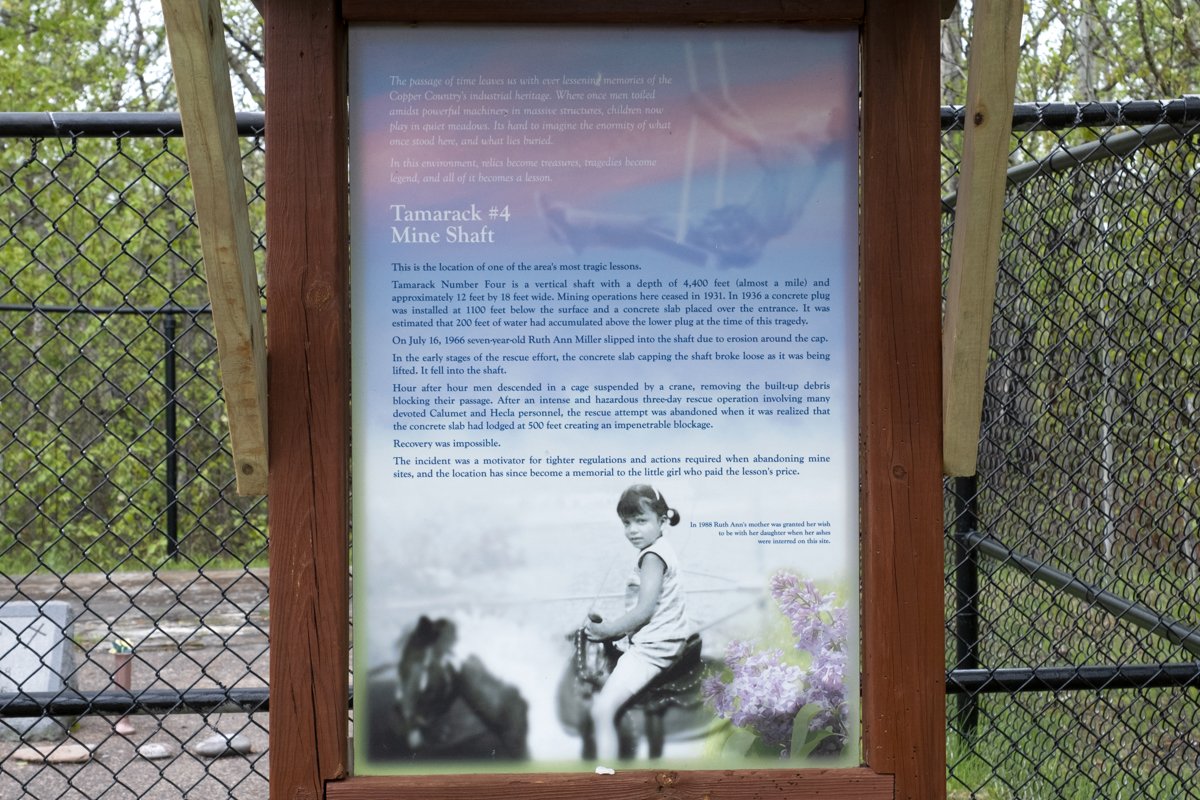

On July 16, 1966, 7-year-old Ruth Ann Miller was playing with her brother, Gary, 10, near the mine cap for Shaft No. 4, picking berries. Gary ran home after Ruth fell into the shaft, telling his parents that the ground had given way underneath her and she had slid into the mine.

Rescue teams began searching for Ruth immediately, though many knew there was little chance of her survival or finding her body, considering the size of the shaft. Rescue teams found a concrete cap roughly 400 feet below the entrance cap. There was debris on that, and while trying to remove the cap, it went crashing down to the bottom of the shaft. Rescue crews were bogged down by rotting timbers and other debris on the way down, the cause of dozens of deaths in the mines over the decades. Experts estimated that there was likely 1,000 feet of water at the bottom of the shaft.

The search was called off on Tuesday, July 19, 1966. Federal officials said the descent into the mine was too dangerous. Crews had made it some 1,000 feet into the shaft. Workers at the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company staged a small strike to protest the ending of the search, though they returned to work when they learned that Ruth’s mother and stepfather agreed that the search was becoming too dangerous.

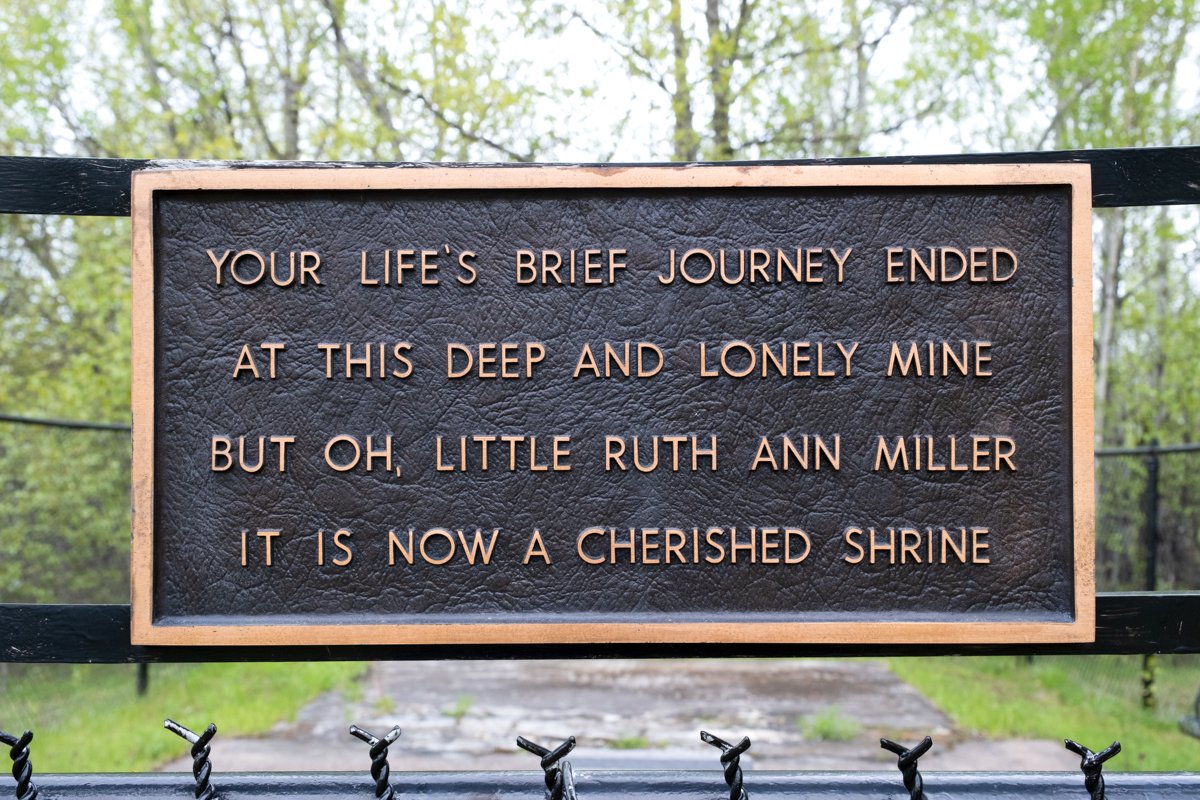

On July 21, 60 people gathered at the top of Tamarack Shaft No. 4 to hold final rites for Ruth Ann Miller. Within days, bundles of flowers appeared on the mine’s entrance cap. Late that fall, a simple marker was placed on the top of the cap, which remains there today. Her family, including her mother, Ruth Vivian Taylor, maintained the grave.

When she passed in 1988, Taylor’s cremated remains were interned next to her daughter’s grave. Her son, Gary, Ruth’s brother, the last person to see her alive, was cremated and interned next to his family at the cap with his mother and sister in 2022. Ruth’s stepfather, Eugene Taylor, also plans to be interned here.

Modern-Day Tamarack Mine Shaft #4

Today, the mine cap is still there and is fenced off. Ruth Ann Miller’s headstone is the highlight, but there are markers for her mother and brother. There are flowers, other memorial items, and an informational placard about what happened to Ruth and her family.

To get to the memorial, take North Tamarack Road from downtown Calumet, passing North Tamarack Park. Just before Amygdaloid Road, there’s a two-track on the left. Follow that a short distance, and you’ll be deposited into a small parking area next to the fenced-in mine shaft.

This is one of the saddest places I’ve visited in the Keweenaw Peninsula. Still, it’s a worthy stop on your trip, as it’s a very real part of Copper County’s history. For decades, hard-working people died in the mines, and for decades after the mines closed and people lost their jobs, mine shafts were left unsupervised and abandoned.

Ruth Ann Miller was born in 1958, and there are still people alive who knew her. If you choose to visit Ruth Ann Miller’s Memorial, be thoughtful and courteous.